The following article has been published as part of a series celebrating 550 years since St Catharine’s was founded in 1473.

Each year on 25 November, the St Catharine’s community remembers and gives thanks for Robert Woodlark, who founded a College on that day in 1473 to honour Saint Catharine of Alexandria. During our 550th anniversary celebrations, it seems appropriate to reflect upon the College’s historical inheritance and how university life has changed since 1473.

Dr Christa Lundberg (2022), Dame Jean Thomas Junior Research Fellow at St Catharine’s, specialises in the history of early modern universities, books and knowledge. During her PhD studies, she looked closely at the University of Paris during the early modern period. We asked her about the events of 1473 in higher education and the context in which St Catharine’s was founded.

In terms of the history of universities, is there a particular event in 1473 that stands to you?

“The most remarkable event at the University of Paris that year was that Louis XI of France decided to prohibit the teaching and study of nominalism. Nominalism was a philosophical school associated with William of Ockham and the view that universals exist only as concepts in the mind and not in reality. The royal decree issued in March boiled down to two demands: 1) the University of Paris should not teach nominalist authors and 2) its academics should turn in nominalist books to the Crown for safekeeping.”

Given monarchs appetites for power in France and indeed other countries in the early modern period, why is this intervention remarkable?

“Louis XI’s decree is not typical of the time or afterwards – it was rare for monarchs to intervene in university affairs. In this case, however, the King was not concerned with the philosophical curriculum but with religious policy. At the time some theologians argued that nominalism had heretical implications. Likely some of them, including Louis’s confessor, convinced him to enact the ban. The King didn’t just see himself as defender of the faith, a title claimed by other monarchs throughout history; he also sought to be the ‘most Christian king’, essentially competing with the Pope to command authority over the Church. In this context, we can see the decree as a way for him to exercise oversight of theological scholarship."

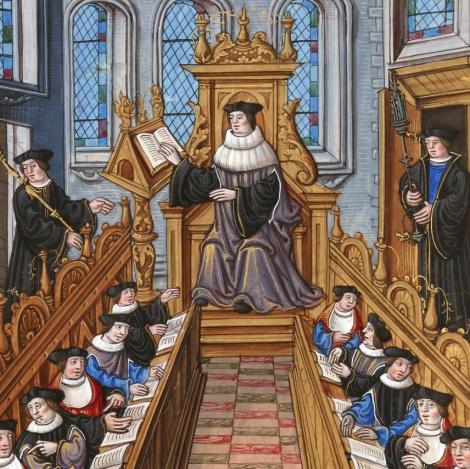

|

|

|

Was he successful?

“We have limited evidence about how people reacted to the ban. We have a ‘Defence of nominalism’ written shortly after the ban that argues against the view that their philosophy leads to heresy. Archival documents suggest that university teachers were willing to swear an oath not to teach nominalism but that they resisted handing over their books. Books were of course valued possessions. Moreover, I suppose that academics at the time were more used to accepting restrictions concerning what they could teach than what they read or discussed. Although the University’s Faculty of Theology had some limitations of its own on what you could say in debates, there was generally much greater leeway in such situations.

“The decree actually ends up being withdrawn by Louis in 1481, in the final years of his reign. At this point we’re in a very different place culturally compared to 1473, and Louis is listening to a different set of trusted advisors. By the 1490s, which is the start of the period I studied for my PhD, academics are working freely and happily on nominalist authors and it is a changed climate.

“A few decades later, of course, debates about heresy emerge again with new force. During the Reformation, the University of Paris doubles down as a guardian of orthodoxy and takes on a mission to combat Martin Luther and any other author they suspect of heresy. By this time, ironically, the Faculty of Theology is working in opposition to French monarchs, some of whom are more attuned to Luther and evangelical thought.”

Broadly, how do the University of Paris and St Catharine’s compare at their foundation?

“At first glance, they are very different: the University of Paris is founded around 1150, some 323 years before St Catharine’s. Look deeper though and you’ll find shared religious motivations for founding both institutions.

“Robert Woodlark taught theology at the University of Cambridge and founded St Catharine’s, specifically to further the study of philosophy and theology. As an indicator of the College’s reputation for theology and connections to the Church of England, it wasn’t until 1927 that the Fellows elected a Master who had not been/would not later be ordained as a member of the clergy.

“Meanwhile, the future University of Paris started out as a student-teacher corporation operating as an annex of the Notre-Dame cathedral school, and the Church remained a significant employer of graduates for centuries. It’s at this point I’ll note that a doctorate in theology used to take nine years of study!”

What other events in 1473 affect both the University of Paris and St Catharine’s?

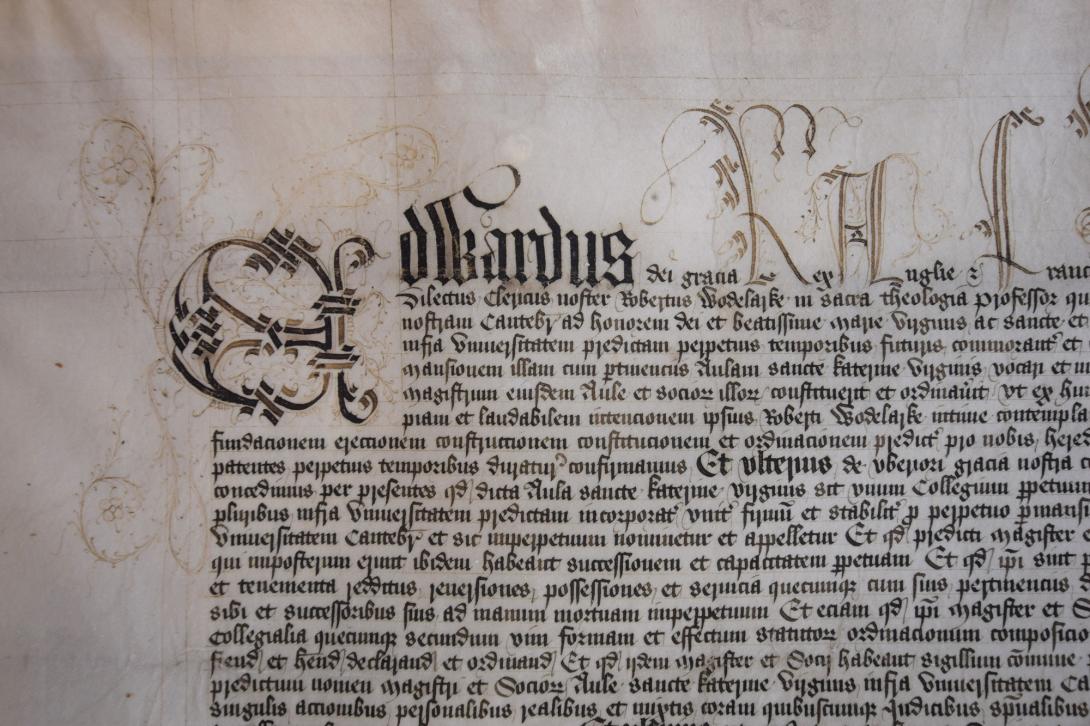

“Conflict between the monarchs of France and England has a variety of knock-on effects for both Catz and Paris. First, anti-English sentiments were a clear factor in the debates around Ockham and nominalism, with the French reluctant to adopt English philosophy. Second, the cost of war with France may be one reason why no members of the royal family were involved in the foundation of Cambridge Colleges between 1465 and 1511: following closely behind Catz, Jesus College was established as a religious institution by the Bishop of Ely in 1496. Finally, the impact of war between England and France is evident again in the 1475 Royal Charter of St Catharine’s College, which is signed by the infant Prince of Wales because Edward IV is the other side of the Channel negotiating a peace treaty with Louis XI.”

Why do you find this specific period in the history of early modern universities so fascinating?

“The late 15th century is a relatively neglected period of history. Because it falls before the Renaissance and the Reformation, it can be overlooked or characterised as a period in which scholastic philosophy or theology were in decline – unfairly in my view. I think historians simply haven’t looked hard enough to find sources that would tell us more about universities at that time. For the University of Paris in particular, there are still important new documents to be found in libraries across Europe. This is in part because so many institutions were reformed and broken up during the French Revolution. For example, the medieval Parisian colleges no longer exist and their archives, to the extent that they survive, are scattered. By contrast, St Catharine’s has a much more continuous history. This is one reason why being part of this college community is so rewarding for my research – while much has changed, some aspects of college life still put me in direct contact with the institutions I study.”